New York Times Magazine Reveals the Double Dose of Danger in The Women's War

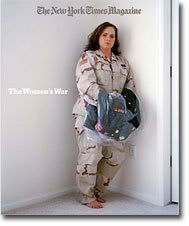

Sara Corbett delivers a troubling yet must-not-miss cover feature in today's Sunday magazine: The Women's War. Your journey over will bring you something of great depth and breadth (16 full web pages worth), alongside a rich multi-media presentation introducing you to the unique dangers many women in today's military face. On the cover, former Wisconsin Army National Guardswoman Keri Christensen.

Sara Corbett delivers a troubling yet must-not-miss cover feature in today's Sunday magazine: The Women's War. Your journey over will bring you something of great depth and breadth (16 full web pages worth), alongside a rich multi-media presentation introducing you to the unique dangers many women in today's military face. On the cover, former Wisconsin Army National Guardswoman Keri Christensen.

Christensen's story joins that of Suzanne Swift, the Fort Lewis, Wash., specialist who went AWOL as her unit redeployed to Iraq; fellow Wisconsin Army National Guardswoman Abbie Pickett; Keli Frasier, an Army reservist from Colorado; Amorita Randall, a former naval contruction worker; and Kathleen, a 37-year-old Army nurse who had spent her time in Iraq treating badly-injured Iraqis, many of them children.

All have a story to tell. Courageous women and reporting...

Click on 'Article Link' below tags for more...

In the interest of education, article quoted from extensively.

From the NYT:On the morning of Monday, Jan. 9, 2006, a 21-year-old Army specialist named Suzanne Swift went AWOL. Her unit, the 54th Military Police Company, out of Fort Lewis, Wash., was two days away from leaving for Iraq. Swift and her platoon had been home less than a year, having completed one 12-month tour of duty in February 2005, and now the rumor was that they were headed to Baghdad to run a detention center. The footlockers were packed. The company's 130 soldiers had been granted a weekend leave in order to go where they needed to go, to say whatever goodbyes needed saying. When they reassembled at 7 a.m. that Monday, uniformed and standing in immaculate rows, Specialist Swift, who during the first deployment drove a Humvee on combat patrols near Karbala, was not among them. ...

The weekend before the deployment was to start, however, Swift drove south to her hometown, Eugene, Ore., to visit with her mother and three younger siblings. The decision to flee, she says, happened in a split second on Sunday night. "All my stuff was in the car," she recalls. "My keys were in my hand, and then I looked at my mom and said: 'I can't do this. I can't go back there.' It wasn't some rational decision. It was a huge, crazy, heart-pounding thing."

For two days after she failed to report, Swift watched her cellphone light up with calls from her commanders. They left concerned messages and a few angry ones too. She listened to the messages but did not return the calls. Then rather abruptly, the phone stopped ringing. The 54th MP Company had left for Iraq. Swift says she understood then the enormity of what she'd just done.

She was eventually arrested after a winter and spring on the run, her actions always hanging over her head yet seeing a Eugene therapist at her mother's urging every week. But Swift wasn't just running from combat duty: she claimed she feared returning to the sexual harassment she had experienced at the hands of multiple commanding officers.In a written statement to investigators, Swift asserted that her station, Camp Lima, outside Karbala, was hit by mortar attacks almost nightly for the first two months of her deployment. She reported working 16-hour shifts, experiencing the death of a fellow company member in an incident of friendly fire and having a close friend injured in a car bombing. What Swift said distressed her most, however, was a situation that involved her squad leader, the sergeant to whom she directly reported in Iraq. She claimed that he propositioned her for sex the first day the two of them arrived in Iraq and that she felt coerced into having a sexual relationship with him that lasted four months - the relationship consisting, she said, of his knocking on her door late at night and demanding intercourse. When she finally ended this arrangement, Swift told me, the sergeant retaliated by ordering her to do solitary forced marches from one side of the camp to another at night in full battle gear and by humiliating her in front of her fellow soldiers. (The sergeant could not be reached, but according to an internal Army report, he denied any sexual contact with Swift.)

As it often is with matters involving sex and power, the lines are a little blurry. Swift does not say she was raped, exactly, but rather manipulated into having sex - repeatedly - with a man who was above her in rank and therefore responsible for her health and safety. (Some victims' advocates use the term 'command rape' to describe such situations.) Swift says that the other two sergeants - one in Kuwait and one back home in Fort Lewis, both a couple of ranks above her - made comments like "You want to [expletive] me, don't you?" or when Swift asked where she was to report for duty, responded, "On my bed, naked."

Following her arrest last summer, there was a large outpouring of support for Swift. Many other female veterans came forward -- their service spanning several decades -- to tell of their own experience of sexual harrassment or rape.

From an August 12, 2006, press conference:

Continuing, from the NYT piece:In the wake of several sex scandals in the 1990s, the U.S. military has tried to become more sensitive to the presence of women, especially now that they fill 15 percent of the ranks worldwide. There are regular mandated workshops on preventing sexual harassment and assault. Each battalion has a designated Equal Opportunity representative trained to field and respond to complaints. Swift said she initially reported what she characterized as an unwanted relationship with her squad leader in Iraq to her Equal Opportunity representative there, who listened - she claims - but did nothing about it. (According to the internal report, the E.O. representative told investigators that he asked Swift if she had a complaint to make but that she declined at the time.)

Swift made it clear that since enlisting in the Army when she was 19, she'd grown accustomed to hearing sexually loaded remarks from fellow enlisted soldiers. It happened "all the time," she said. But coming from her superiors, especially far away from the support systems of home and against a backdrop of mortar attacks and the general uncertainties of war, the overtones felt more threatening. "You can tell another E-4 to go to hell," she said, referring to the rank of specialist. "But you can't say that to an E-5," she said, referring to a sergeant. "If your sergeant tells you to walk over a minefield, you're supposed to do it."

And so, while the tension may ever exist underneath the surface, the unique conditions in Iraq and Afghanistan -- where drinking is illegal and local women are not sexually accessible to men as they were in past conflicts -- make the tension between men and women serving alongside each other all the more dangerous. For women, this means a "double whammy" of military sexual trauma and combat exposure which can lead to a further increase of PTSD.More than one-quarter of female veterans of Vietnam developed PTSD at some point in their lives, according to the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Survey conducted in the mid-'80s, which included 432 women, most of whom were nurses. (The PTSD rate for women was 4 percent below that of the men.) Two years after deployment to the gulf war, where combat exposure was relatively low, Army data showed that 16 percent of a sample of female soldiers studied met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, as opposed to 8 percent of their male counterparts. The data reflect a larger finding, supported by other research, that women are more likely to be given diagnoses of PTSD, in some cases at twice the rate of men.

Experts are hard pressed to account for the disparity. Is it that women have stronger reactions to trauma? Do they do a better job of describing their symptoms and are therefore given diagnoses more often? Or do men and women tend to experience different types of trauma? Friedman points out that some traumatic experiences have been shown to be more psychologically "toxic" than others. Rape, in particular, is thought to be the most likely to lead to PTSD in women (and in men, in the rarer times it occurs). Participation in combat, though, he says, is not far behind. ...

A 2003 report financed by the Department of Defense revealed that nearly one-third of a nationwide sample of female veterans seeking health care through the V.A. said they experienced rape or attempted rape during their service. Of that group, 37 percent said they were raped multiple times, and 14 percent reported they were gang-raped. Perhaps even more tellingly, a small study financed by the V.A. following the gulf war suggests that rates of both sexual harassment and assault rise during wartime. The researchers who carried out this study also looked at the prevalence of PTSD symptoms - including flashbacks, nightmares, emotional numbing and round-the-clock anxiety - and found that women who endured sexual assault were more likely to develop PTSD than those who were exposed to combat. Abbie Pickett, whom I had the pleasure to briefly meet last year and who contributed her story in my upcoming book, returns the focus to the tensions that are kicked up a notch in a combat zone between the men and women who are serving:

Abbie Pickett, whom I had the pleasure to briefly meet last year and who contributed her story in my upcoming book, returns the focus to the tensions that are kicked up a notch in a combat zone between the men and women who are serving:During her 11-month stint in Iraq, stationed mostly outside Tikrit in a company of 19 women and 140 men, Pickett claimed her male peers thought nothing of commenting on her breast size or making sexual jokes about her. She regularly encountered porn magazines sitting in the latrines and in common areas. None of this behavior was particularly new to her; it was life as she knew it in the military. Yet in a war zone the effect seemed more corrosive. "The real difference is that over there, there's never a break from it," Pickett told me. "At home, you can go out with your girlfriends and get a beer and talk about the idiots who were cracking jokes. Over there, you're a minority 24 hours a day, seven days a week. You never get that 10 minutes to relax or even cry. Sometimes you just need to let it all out."

One night in the fall of 2003, Pickett recalled, her unit endured a mortar attack. Trained as a combat lifesaver, she spent part of the night tending to bleeding soldiers by flashlight in a field tent. Once the experience was over, the memory kept replaying in her mind. "For a long time, I wished I had died that night," Pickett told me, adding that she returned to her home in Wisconsin and was "barely functioning"- unable to sleep or concentrate. She spent days alone inside her apartment, not talking to anyone. "I was draining everyone around me," she says. A year after her deployment, a V.A. clinician formally diagnosed PTSD, which Pickett says she thinks stems from the stress of combat, harassment and the earlier sexual assault. If Vietnam became notorious as a war that combined violence and sex, with Southeast Asian brothels being the destination of choice for soldiers on temporary leave from the war, the sexual politics of the Iraq war are, as of yet, unclear.

Keri Christensen, the National Guardswoman pictured on today's cover, had 13 years of part-time service under her belt before being deployed to Iraq in 2004.Prior to her deployment in Iraq, she loved her role in the military. "Before we were married, my husband was in awe of it," she said, laughing. "He was like, 'I met this girl and she hauls tanks!'" She added that she was good at what she did, receiving several awards over the years. Beyond commitment to the Guard of one weekend a month and two weeks' training each summer, Christensen spent the previous six years as a stay-at-home mom. Her life, she said, had been a generally happy one.

But the stresses of deployment were surprisingly manifest: she agonized over leaving her daughters, who were then 6 and 2 years old. Stationed in Kuwait, Christensen's unit ran convoys of equipment back and forth from the port to inside Iraq. "It was really scary," she said, explaining that her convoy had been mortared during an early mission. "But it was like, Hey cool, we're on a mission." Then one day in February 2005, Christensen was accidentally dragged beneath a truck trailer and run over, breaking a number of bones in her foot and injuring her knee and back. She was assigned to a desk job in a tent in Kuwait, mostly working the night shift. It was there, she said, that a sergeant above her in her command - a man she'd known for 10 years - began making comments about her breasts and at one point baldly propositioned her for sex.

Something inside of her broke, she said. Christensen claims that she was punished for even mentioning the situation to her company commanders - written up for minor infractions; accused, she says falsely, of being intoxicated (for which she was demoted); and reassigned for duty to an airfield near a mortuary, where she occasionally helped load coffins of dead soldiers onto planes bound for the U.S. (The Wisconsin Army National Guard denied that Christensen was punished for making a sexual-harassment claim and stated that the claim was investigated and dismissed for lack of evidence.) Christensen says that a combination of war stress, harassment and the reprisals that followed were so upsetting and demoralizing that she considered suicide on several occasions. Her military records show that during her deployment, she was given a diagnosis of depression and PTSD. ...

Christensen had been home from war then for just over a year, having returned to her life as a stay-at-home mother, yet she could not shake what the deployment had done to her - the accident, the confusion and shame of her sexual harassment, and then what she felt was an ignominious demotion and marginalization after reporting the incidents. And while there are those whose image of PTSD is still tied to Vietnam War movies - the province of men who earned their affliction only after having their best buddies die in their arms in a gush of blood - Christensen shares the same diagnosis. That is to say that no matter what constituted her war experience, the aftermath was much the same. She suffered from severe headaches and forgetfulness. "I feel like I'm always forgetting something," she said. "I leave the house and I don't know if I've left something on - the stove or a candle. I can't trust my memory." She told me that her 8-year-old, Madison, recently had to tell her the family's new phone number. She'd lost friends and had 'rough spots' with her husband. Afraid of crowds, she started grocery shopping at 6 in the morning and was having her mother buy clothes for her children. Driving, too, made her fearful, since she felt 'foggy' and more than once ran a stop sign or a red light with her kids in the car. Though she went for counseling and medical treatment at a local V.A. while living in Illinois after she returned from Iraq, Christensen had not yet found her way to the Denver V.A. for treatment. The thought of getting in her car and making the 20-minute drive petrified her. CBS Evening News interviewed Chistensen back in January. Click on the image to the left to access the video player on the CBS page for her interview. Please read the whole NYT piece for additional stories told by the featured women. Unbelievably, I've only scratched the surface.

CBS Evening News interviewed Chistensen back in January. Click on the image to the left to access the video player on the CBS page for her interview. Please read the whole NYT piece for additional stories told by the featured women. Unbelievably, I've only scratched the surface.

Additional OEF/OIF PTSD stats

- Female OEF/OIF troops who have served since 2001: 160,500

- Female-to-male ratio: 1-in-7

- Portion of female troops in military: 15%

- OIF WIA: at least 450

- OIF KIA: 75 (as of Mar. 7, 2007)

- OIF females KIA as a percentage of total count: 2.18%

- Cases of reported military sexual assaults, 2005: 2,374

Related Posts