Study Finds PTSD Risk Rooted in Stress as Neuroscience Field Bids Farewell to "Patient H.M."

Last week, Henry Gustav Molaison -- a name most would not recognize even though he was the neuroscience field's most famous of patients -- passed away at the age of 80. Since 1953, when experimental brain surgery to alleviate severe epileptic seizures severely damaged his ability to lay down new memories, Molaison was known simply as "H.M."

From Wikipedia:

Henry Gustav Molaison (February 26, 1926 – December 2, 2008), better known as HM or H.M., was a memory-impaired patient who was widely studied from the late 1950s until his death. His case played a very important role in the development of theories that explain the link between brain function and memory, and in the development of cognitive neuropsychology, a branch of psychology that aims to understand how the structure and function of the brain relates to specific psychological processes.

Before his death, he resided in a care institute located in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, where he was the subject of ongoing investigation. Audio recordings from the 1990s of him talking to scientists were released in early 2007. Henry loved to do crossword puzzles, play bingo, watch TV, and socialize with the people who took care of him.

Not surprisingly, in February 2007, NPR's Weekend Edition [listen] introduced their audience to the man whose ill-fated surgery gave scientists a clearer window into the body's most complex and vital organ: the brain. The program also provides a short introductory primer on memory and the brain.

Due to PTSD and memory's unique relationship -- with past traumatic experiences feeling vivid, painfully immediate and even more "real" than recent events rather than the distant memories they should be for its sufferers -- H.M. (who was an "n of 1," or the only person who is known to have had the surgical procedure performed on him; therefore, the only one available in this specific research pool) increased our knowledge base in this area, too.

In extended, a journey into the world of Molaison's amnesia, along with a host of fresh research coming out on the subject.

In educational interest, article(s) quoted from extensively.

Introduced in the NPR program mentioned above was Joanna Schaffhausen, the neuroscientist who wrote her PhD dissertation on her famous patient, and spent 40 years at his side. She writes of him in Brain Connection:

When twenty-seven year old Henry M. entered the hospital in 1953 for radical brain surgery that was supposed to cure his epilepsy, he was hopeful that the procedure would change his life for the better. Instead, it trapped him in a mental time warp where TV is always a new invention and Truman is forever president. The removal of large sections of his temporal lobes left Henry unable to form any new personal memories, but his tragic loss revolutionized the field of psychology and made "H.M." the most-studied individual in the history of brain research.

Henry grew up outside of Hartford, Connecticut, and was by all accounts an amiable young man with above average intelligence. He liked to go ice skating and to listen to mystery shows on the radio, which he enjoyed because he could often deduce the villain ahead of the program detective. Then on his sixteenth birthday, Henry had his first grand mal seizure during a celebratory trip to the city with his parents. After that point, the paralyzing seizures arrived with increasing frequency, until by the summer of 1953, he was experiencing as many as eleven episodes per week. He was unable to hold a steady job, and his prospects for independent living seemed dim. There were not many effective treatments available for epilepsy in 1953, so it was with a mixture of hope and trepidation that Henry's family turned to Dr. William Scoville and his experimental surgery.

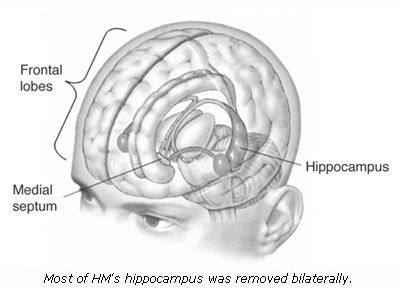

The idea behind the surgery was simple. Seizures, as Scoville correctly reasoned, are caused by uncontrolled electrical impulses that start in a localized area and then spread throughout the rest of the brain. If one could remove the part of the brain where the seizures originated, it should be possible to cure the epilepsy. Henry had the most common form of the disease, called temporal lobe epilepsy, which meant that his seizures began in the tissue located on either side of his brain.

Dr. Scoville removed a large chunk of Henry's right and left temporal lobes, which was a crucial decision because the brain is symmetrical and thus most important structures are duplicated. Altogether, Henry lost about a fist-sized portion of his brain, which encompassed (on both sides) the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the entorhinal and perirhinal cortices. As it turns out, the hippocampus is crucial for memory storage. When he lost his hippocampi, Henry became frozen in 1953, remembering very well the events before his operation but unable to create any new memories. He describes the experience like this:

"Right now, I'm wondering, have I done or said anything amiss? You see, at this moment everything looks clear to me, but what happened just before? That's what worries me. It's like waking from a dream. I just don't remember."

While H.M.'s brain functions were altered as a result of physical effort during the surgical procedure, psychological damage has been shown to have an effect on the hippocampus region as well:

Psychological trauma has great effects on physical aspects of patients’ brains, to the point that it can have detrimental effects akin to actual physical brain damage. The hippocampus...is involved in the transference of short term memories to long term memories and it’s especially sensitive to stress. Stress causes glucocorticoids (GCs), adrenal hormones, to be secreted and sustained exposure to these hormones can cause neural degeneration. The hippocampus is a principal target site for GCs and therefore experiences a severity of neuronal damage that other areas of the brain do not[7].

In severe trauma patients, especially those with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, the medial prefrontal cortex is volumetrically smaller in size than normal and is hyporesponsive when performing cognitive tasks, which could be a cause of involuntary recollection (intrusive thoughts)[8]. The medial prefrontal cortex controls emotional responsiveness and conditioned fear responses to fear-inducing stimuli by interacting with the amygdala. In those cases, the metabolism in some parts of the medial prefrontal cortex didn’t activate as they were supposed to when compared to those of a healthy subject.

J. Douglas Bremner, the director of Emory University's Center for Positron Emission Tomography and an associate professor of psychiatry and radiology at Emory's school of medicine, explains how patient H.M. moved neuroscience field's understanding of PTSD forward in his book, "Does Stress Damage the Brain?: Understanding Trauma-Related Disorders from a Neurological Perspective."

First, a bit of background:

Working as Medical Director at the VA's first specialized post-Vietnam hospital-based treatment program in West Haven, Conn., Bremner noticed that patients were consistently missing counseling appointments. When asked about this, they relayed that they simply forgot about them.

While the unit's psychiatrists chalked all of this up to their unconscious resistance to treatment, Bremner wasn't so sure. After having observed "damaging effects of glucocorticoids released during stress on the hippocampus" in firemen, he wondered if his vets were also suffering the same stress-induced brain damage.

From "Does Stress Damage the Brain?," p. 112-113:

Another thing I noticed about these patients is that they remembered things that happened in Vietnam very vividly. One of my patients would bring me scrapbooks with pictures of him and his friends in Vietnam. He would talk about his friends as if he had seen them the day before. However, he couldn't remember what he had for breakfast that morning, and could only vaguely describe what was going on in his current daily life. ...

These PTSD patients appeared to be suffering from an inability to learn new things. However, their memories of long-ago events were intact. These patients were very similar to patients suffering from what we call neurological amnesia, which is caused by strokes or tumors that specifically affect the hippocampus.

A well-known example of this is the patient H.M., who had strokes affecting the hippocampus on both sides of his brain. He could carry on normal conversations, and remember everything that happened in his life very clearly before the stroke occurred. However, since the time of the stroke he couldn't learn anything new (Scoville & Milner, 1957). [Ed. note: My understanding is that the surgery to prevent H.M.'s frequent strokes is what damaged the area of the brain related to memory, not the stroke itself.]

He spent his days reading one copy of the Reader's Digest. When he got to the end, since none of the articles stayed in his memory, he would just start all over again. [...] My patients with PTSD have similar experiences.

Based on the observations and the studies of the effects of stress on the hippocampus, my colleagues and I became interested in studying memory disturbances in our PTSD patients. We administered tests of memory, such as remembering a story or a list of words, that had been shown to be related to neuron (the basic cells of the brain) loss in the hippocampus. [...]

These studies led us to conclude that stress may have resulted in damage to the hippocampus in PTSD patients, and that this could explain the memory problems we had observed. PTSD patients have trouble remembering things like what to buy at the grocery store, or appointments they have made.

(Even more alarming: Those suffering with PTSD may also have difficulty remembering to take or recalling if they've already taken their medications, which may lead to under- or over-medication.)

Recent studies related to memory loss and PTSD:

- In August 2006, a study revealed that "Iraq [veterans] are more likely than other U.S. soldiers to suffer mild memory and attention lapses back home, but they also tend to have better reaction time, at least in the short-term, a study found. ... The study involved 654 soldiers who took mental-function tests a few months before going to Iraq in mid-to-late 2003 and within three months after returning in 2005. The researchers noted subtle changes in their scores. If the changes persist, "that's where you have to worry about people developing stress-related emotional problems like post-traumatic stress disorder," Vasterling said."

- In January 2007, a study involving New Yorkers in the vicinity of the September 11 attack found that "people who were within about two miles of Ground Zero on that day now retain especially vivid, detailed recollections of the scenes and events of that morning -- a kind of recall that experts call "flashbulb memories." Brain imaging suggests that these memories are especially strong because the amygdala -- a brain area focused on fear and memory -- kicked into high gear as these people watched that morning's catastrophic events unfold."

- In February 2007, a study suggested "hyperactivity in a region of the prefrontal cortex might contribute to disorders of learned fear in humans, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. While building on previous findings, the study contradicts prior thinking that the amygdala, which plays a central role in emotional learning, is sufficient for processing and expressing fear. The findings, say the researchers, open the potential for new avenues of treatment."

- In April 2007, a study "evaluated 15 pre-adolescent children with symptoms of PTSD, including nightmares and uncontrollable flashbacks, extreme agitation and emotional numbness. ...They found that kids with more severe PTSD symptoms had more cortisol in their blood and their hippocampi decreased in volume. "What that means is that the higher your symptoms of PTSD, or the higher your level of cortisol, the higher your chances of having a decrease in the size of this structure," Carrion notes, adding that this was the first time researchers have really seen that connection, indicating how cortisol might be related to the hippocampus."

A decade-long study into post-traumatic stress disorder among combat veterans and their identical twins has yielded critical information on the root causes of this devastating condition.

The researchers found that both genetic and environmental factors increase the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The work, to be presented Tuesday at the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting in Scottsdale, Ariz., was sponsored by both the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health and the Veterans Administration.

"In addition to building our understanding of how PTSD comes to exist, we may have useful signs for PTSD prevention and treatment," study author Dr. Roger Pitman, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, said during a recent teleconference on the research. "For example, persons with recognized PTSD risk factors may be best advised to avoid occupations that would have them serve in highly stressful situations, such as serving in military forces. Things acquired as a result of stress are more likely to be reversed by treatment and could be taken as targets of PTSD treatment."

Scientific American also chimed in yesterday with an important piece called "The Amnesia Game" by Rajamannar Ramasubbu:

...[I]n some individuals, extremely stressful or traumatic events can induce amnesia, so that they lose the ability to remember what happened. In some instances this loss can lead to the erasure of a vast amount of memory, so that people even forget basic facts about their identity, such as where they live or what their name is.

Amnesia induced by negative emotions is considered a psychological defense mechanism that protects the organism from the consequences of extreme trauma and catastrophic fear. However, recent studies suggest that emotion induced memory loss can also prevent appropriate coping mechanisms, so that people never learn to deal with their painful emotions. (Even if these emotions can’t be recalled, they can still linger below the surface and have psychological consequences.) Hence, understanding how negative emotions induce amnesia, and why only some people who are exposed to traumatic events develop emotion induced amnesia, may have clinical and preventive implications. ...

[In a new study] authors conclude[d] that emotion induced memory is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple genes. Although serotonin transporter genes may play a role in regulating emotion induced retrograde amnesia, they do not seem to underlie all forms of emotion-induced memory loss.

The amygdala is a brain region critical for the experience and expression of emotion as well as for the consolidation of emotional memory. At a modest level of activation, the amygdala seems to augment the function of the hippocampus, a brain region involved in the formation of long-term memory. When the amygdala is greatly excited, as during traumatic events, however, hippocampal function is inhibited and memory impairment is triggered. ...

One potential implication of this research involves preventative genetic testing. By screening high risk subjects for the 5-HTTLPR short variant genotype—including in military personnel or survivors of childhood trauma—doctors and therapists can better focus their energies. In theory it should also be possible to develop medications or cognitive strategies that regulate or suppress the expression of serotonin transporter short variant genes, which should be useful in preventing and treating PTSD or other stress induced psychiatric disorders.

Well, that's a lot of data for any tired, old brain to absorb. But, good news arrived last month on the benefits of being online:

A new UCLA study, part of the growing research into the effects of technology on the brain, shows that searching the Internet may keep older brains agile - it's like taking your brain for a walk. It's too early to conclude that technology will help vanquish Alzheimer's disease, but "our study shows that when your brain is on Google, your neural circuitry changes extensively," said psychiatrist Gary Small, director of UCLA's Memory & Aging Research Center.

The new study, which will be published next month in the Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, comes at a time when medical experts are forecasting that Alzheimer's cases will quadruple by 2050. In response to such projections, "brain-gyms" and memory-building computer programs have proliferated.

The subjects in Small's nine-month study were 24 neurologically normal volunteers ages 55 to 76, with similar education levels. They were assigned two tasks: to read book-like text on computer screens and to perform Internet searches. ...

MRI results showed that both text reading and Internet searching stimulated the regions of the brain controlling language, reading, memory and vision. But the Internet search lit up more areas of the brain, additionally activating the regions controlling complex reasoning and decision making. The increased brain activity, which is probably due to the many rapid choices such searches involve, suggests that subjects had a richer sensory experience and heightened attention.

By focusing on older users, Small said, he aimed to fill a gap in brain research. Few studies have looked at the effects of technology on these "digital immigrants," who began using computers later in life than their younger counterparts, the "digital natives." Small's study was started as part of the research for his latest book, "iBrain: Surviving the Technological Alteration of the Modern Mind."

"Our findings point to an association between routine Internet searching and neural circuitry activation in middle-aged and older adults," the study said. "Further study will elucidate both the potential positive and negative influences of these technologies on the aging brain." The implications are provocative, particularly because it is well known that developments in technology affect human behavior.

"People who are more adept with the technology will be more successful in society, and their offspring will be more likely to excel," Small told The Chronicle.

Cheers to massaging that brain muscle!

Related Posts

- Study: Specific Brain Chemical Appears to Influence Individual Resiliency and Stress Reaction

- Studies: Veterans and Alcohol, PTSD's Effect on the Heart, Tuberculosis Drug Shows Promise in Reshaping Traumatic Memories

- Study: Specific Brain Chemical Appears to Influence Individual Resiliency and Stress Reaction

- Neuroscience Study: Prefrontal Cortex Hyperactivity in Brain Associated with Learned Fear, PTSD

- A Sample of the Latest PTSD Study Results

- Study: Higher Memory, Attention Lapses for OIF Vets

- Emory University Investigates New Iraq Vet PTSD Treatment

- Scientists Racing to Ease Painful PTSD Memories