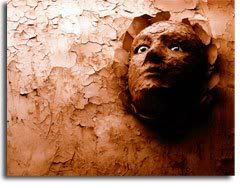

A Real Fright: The Psychological Scars of Combat

It's a standard American ritual. Today, you'll probably be booed at by scary tricksters knocking on your door, demanding sugary treats.

It's a standard American ritual. Today, you'll probably be booed at by scary tricksters knocking on your door, demanding sugary treats.

Perhaps you'll see a chainsaw-wielding demon on the street and laugh. Or maybe you'll dress in scary costumes and get a kick out of reveling in and even poking fun at Halloween's fantasy of fear and death and danger.

Of course, some of us don't have to rely on the eve of All Saints Day to be immersed in dark times and emotions.

Those who've been to war have tapped fear and death and danger on the shoulder. They've lived the more difficult side of life. And many, when they return from the pit of hell, struggle to find the inner and outer security and confidence long since lost to them on some dusty combat trail. Getting their life back isn't as easy as peeling off a costume, wiping off the fake blood or putting away a candy dish.

I wonder what they think about Halloween?

Below the fold, a few recent articles that reveal how the daily fear, anxiety and solitude of PTSD affects some of our recently returned troops. Read as many of them as you can find time for.

In educational interest, article(s) quoted from extensively.

First up, it's the purest of understatements to say that Kelly Kennedy is doing brilliant work over at Military Times. Currently in the midst of publishing a 12-part special report, "Living with PTSD," here's a portion of September's opening installment:

Sgt. Loyd Sawyer joined the Army to bring honor to death.

For years, he had worked as a funeral home director, and his children learned that death was part of the normal cycle of life — that it’s good to mourn for a loved one, and that there was no reason to fear the bodies their daddy embalmed in a workroom of their home.

But then he spent six months working at the morgue at Dover Air Force Base, Del. And then six more months in mortuary affairs at Joint Base Balad in Iraq. ... After that, Loyd no longer saw death as part of a natural cycle.

The faces of dead service members began to haunt his every minute. Awake. Asleep. Some charred or shattered, some with faces he recognized from life, some in parts.

Once, after an aircraft crash, Loyd spent 82 hours lining bodies side by side, the burnt remains still so hot they melted through the plastic body bags.

He took the images home with him, each of the dead competing for space in his mind. He spent hours crying on his family room floor, weeping as his dog Sophie licked away his tears, the only living comfort he could bear.

He pulled back as his sons moved in for hugs and his wife sought the snuggles they had shared daily, hourly, in the past. He lashed out with angry words to increase the distance. He had known his wife, Andrea, since they were each 16, but now he couldn’t even touch her.

They would never understand what he had been through. No one would. Loyd was living a nightmare. And now his family was living one, too.

A clip from the second installment:

When Loyd returned home, he displayed classic symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. His nightmares were so bad that he didn’t sleep — at all. A whiff of diesel or a loud noise sparked flashbacks. He couldn’t be around other people. He couldn’t relate to his wife or two boys. He reacted to everything — a question, a hug, a smile — with anger.

His tour had been filled with mortar attacks, including a rocket that crashed into the windshield of a truck he was driving, as well as processing the bodies of people he knew. Once, a Turkish airplane crashed not 1,000 meters from his mortuary affairs unit, and he spent the next three days packing the still-smoking remains of passengers into body bags.

After months of yelling at his wife Andrea, spending nights crying with his dog, avoiding his kids and refusing to participate in activities he used to enjoy — like barbecues and trips to Disneyworld — he finally came to realize he needed help.

“He knew that something was wrong, and he was very willing to seek treatment,” Andrea said.

He reached out to his chain of command.

“His first sergeant took me seriously when I called for help,” Andrea said. “He called Loyd in the next morning and sent him to see [Army Community Service] about anger management, and they sent him to social services.”

His squad leader worked to keep him busy in a daily routine that would bring no surprises. He made sure Loyd had time to go to his appointments. Then he arrived at the mental health clinic at Fort Lee. And things began to go awry.

Read the article.

Accompanying Military Times videos introduce us to Loyd:

Be sure to bookmark the link to the special report page; there's a lot more content coming in the next weeks and months. Meanwhile, Damien Cave of the New York Times shares the mental anguish of one veteran trying following two tours in Iraq and 20 years of military service:

For Vivienne Pacquette, being a combat veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder means avoiding phone calls to her sons, dinner out with her husband and therapy sessions that make her talk about seeing the reds and whites of her friends’ insides after a mortar attack in 2004.

As with other women in her position, hiding seems to make sense. Post-traumatic stress disorder distorts personalities: some veterans who have it fight in their sleep; others feel paranoid around children. And as women return to a society unfamiliar with their wartime roles, they often choose isolation over embarrassment.

Many spend months or years as virtual shut-ins, missing the camaraderie of Iraq or Afghanistan, while racked with guilt over who they have become.

“After all, I’m a soldier, I’m an NCO, I’m a problem solver,” said Mrs. Pacquette, 52, a retired noncommissioned officer who served two tours in Iraq and more than 20 years in the Army. “What’s it going to look like if I can’t get things straight in my head?” ...

Never before has this country seen so many women paralyzed by the psychological scars of combat. As of June 2008, 19,084 female veterans of Iraq or Afghanistan had received diagnoses of mental disorders from the Department of Veterans Affairs, including 8,454 women with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress — and this number does not include troops still enlisted, or those who have never used the V.A. system. ...

Many women traumatized by combat stress described lives of quiet desperation, alone, in just a few rooms with drawn shades.

Nancy Schiliro, 29, who lost her right eye as a result of a mortar attack in 2005, said that for more than two years after returning home, she rarely left a darkened garage in Hartsdale, N.Y., that her grandmother called “the bat cave.”

Shalimar Bien, 30, described her life, four years after Iraq, as a nonstop effort to avoid confrontation. ... For many female veterans today, war and their roles in it must be constantly explained. For those with post-traumatic stress, the constant demand for proof can be particularly maddening — confirming their belief that only the people who were “over there” can understand them here.

Read full article.

Earlier this month, NPR talked with former Vietnam veteran and Georgia Sen. Max Cleland and shared an excerpt from his new memoir, Heart of a Patriot. Its foreward contains an open letter to America's veterans. Here's a portion of that:

Coming back from military service in a time of war, we may be wounded in ways that don't show to the world at large. Some of the deepest wounds we suffer may be inflicted without leaving so much as a scratch. No matter what you are feeling when you come home, no matter how crazy you feel inside, know that you are not mentally ill. As combat veterans, we have been through some of the most traumatic life experiences possible. War is as close to hell on earth as anything ever could be. That does make us different from our loved ones back home. War marks us all, some more deeply than others. ...

The soldier's lot is to be exposed to traumatic, life-threatening events — happenings that take us to places no bodies, minds, or souls should ever visit. It is a journey to the dark places of life — terror, fear, pain, death, wounding, loss, grief, despair, and hopelessness. We have been traumatized physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. Some of us cope with exposure to hell better than others. Some are able to think of their combat experiences as but unpleasant vignettes in a long and wonderful life. It is not to those veterans I am speaking. I love them, but I am not afraid for them.

I am speaking to the rest of my brothers and sisters, those who find themselves trapped in the misery of memories as I was for so long. For them, I am afraid.

To those veterans I say, you are not alone.

Many of us have been overwhelmed by war. Many of us have been unable to cope on our own with what has happened to us or with what we have done. Many of us have been left hopeless, lost, and confused about ourselves and our lives in ways we never thought possible.

That does not make us victims.

It makes us veterans.

As veterans of war, we are vulnerable to the memories of those experiences for the rest of our lives. Movies, the nightly news, the death of a loved one, even simple stress can serve as a trigger that reminds us of the hell we were once in. Just that remembrance can sometimes be enough to undo all the buckles we used to put ourselves back together when we got home.

Our bodies, minds, and spirits react automatically to these memory triggers. They feel the hurts and fear and horror anew each time. The curse of the soldier is that he never forgets.

Having once felt mortal danger and pure terror, our bodies prepare for it again. That helped us survive on the battlefield. However, what saved us on the battlefield doesn't work very well back here at home. It is impossible to forget our experiences in the military. But it is possible to deal with them positively. It is possible to take control of them.

Here's to conquering those demons...

Related Posts